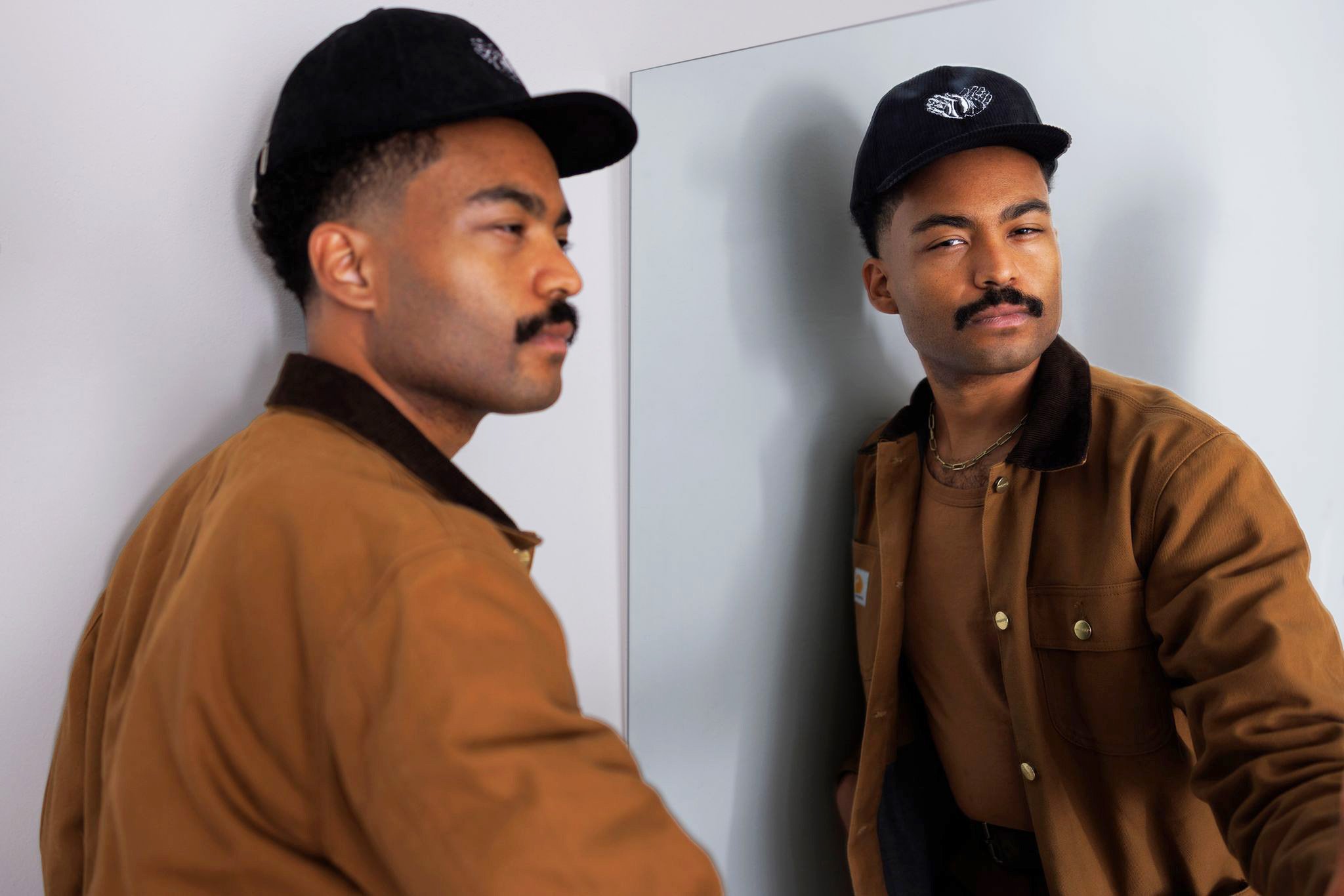

Alex O’Keefe

DISCLAIMER: We do not represent SAG/AFTRA or the WGA in any form. The following are individual opinions only. Please see the SAG/AFTRA or WGA websites for current information on the strikes. Read our #UnionStrong Statement here.

In Conversation with Alex O’Keefe & Josh Gondelman

Photography by Nolwen Cifuentes

Alex: I grew up in Florida, far away from this whole world, pretty poor in the south.

I've been a community organizer since I was a kid. I helped build the Green New Deal movement to stop climate change and also revolutionize the American economy. I was a director's assistant for Jesse Peretz before the Green New Deal. I tried to bring the Hollywood spectacle into politics to get people excited about stuff that used to be boring, like climate change – with the polar bears and icebergs.

I reached a point in politics that felt too polarized, too corrupt - it felt like making a TV show for the worst people on the planet, where there's no character development or growth. I wanted to actually go and change the culture. So, I wrote a pilot and got staffed on The Bear. It wasn’t supposed to be a big show. It was very low budget, and it blew up. And here I am, on strike, trying my best to do the right thing.

Josh: I grew up around Boston in the suburbs. I lived in the city after college for a few years, teaching preschool and doing standup. I moved to New York in 2011 and started doing magazine writing, and internet writing. That, plus some social media attention, got me the ability to start applying for more TV jobs. My first job was a non-union consulting gig on Billy On The Street. Then, I ended up at John Oliver's show in 2014. I did digital work there for a year and social and digital writing. After that, I was a staff writer for the show for four years, and after that, did some work on Mrs. Maisel. I’m still doing standup and writing other stuff, too. The standup was kind of the entry point in the Boston to New York transition, which was what got me to where the jobs and the people are.

Alex: Josh and I met at the very beginning of the strike during a media training.

Josh: We were doing training together, so that's how we came to know each other. To build on that, I feel like as stressful and heavy as this has been — and I don't want to take away from the financial strain it's placed on people in the industry — but, being on the picket line, I've met so many amazing people that I didn't know, people that I would never cross paths with. I'm talking to people in all kinds of television and film writing that I probably will never work in, just because it's not the kind of stuff I do or am good at. It's all these wonderful, amazing people. And that has increased the solidarity working with people like Alex, not in a network-y way, but in a like, “oh shit, there's so many brilliant, wonderful people out there” way. To get to meet them all is a real silver lining during this really intense time.

Alex: Yeah, it's community. I mean, I hate networking. I'm not good at careerism and all that sort of thing. I seek homes. I come from a broken home and a tough community. I’ve always just been searching for a community that I feel safe in and can build in. And writer's rooms are great, but that's not community. It's a job, you know what I'm saying? It has demands. But right now, it’s like there's actual space to be in community and tell our truths to each other.

I felt like, before, you couldn't really talk about class or your economic conditions in Hollywood. It was “beyond the pale.” I was living in New York for eight years, so I'm more of an East coaster. On the West Coast, it’s a lot of trying to get clout and always putting up a front that you're doing good. It's status-minded. But right now, I think all of us have been pushed down a notch. It humbles you, it reminds you of what is actually going on in the world. We're seeing this, especially in LA, this hot labor summer because we're unified – the same boot is crushing all of us right now.

Josh Gondelman on the WGA East picket line.

Alex: What's been special about this strike is that we've been able to hear from voices, because of social media, that you would've never heard from, because we're not at the tippy top of the business. We've been able to represent ourselves.

When I was working on The Bear, I was sitting at this same desk in a tiny Bushwick apartment in Brooklyn, and we had no heat. That pandemic winter, I had a little space heater just to keep my toes warm. That's a degradation of working conditions that you don't expect in Hollywood, but it's called the Dream Factory. Just like any factory, there are demands from the overlords. The overseers wanna get that assembly line running faster, and they don't care if people fall apart trying to assemble the product.

Josh: One of the big things that's happening here is these big multinational, international conglomerates that make billions of dollars in profit every year decided they're changing the distribution model for the work that we're doing. So, instead of porting over a fair, equitable, and sustainable system of compensation, they decided they're going to change the way they distribute. And they're also going to use that kind of transition and chaos as a way to cling to as much profit as they can. It's not fair that just because they change the way they're delivering television and film to people, they don't have to pay writers a fair wage anymore, just because it's a different technology. There are a lot of issues about how the business is done, like shorter seasons, mini-rooms, writers coming in often making below their quote, even if they're very experienced, and then often not getting to see the show through production. That is really difficult.

But fundamentally, these studios are taking this money and playing a shell game. They're going, look over here, there's no money [in streaming]. And you go, well, then why are you putting all your resources into this? We're just asking for money for the work we do. We're not asking for weird free bonus money. We're asking for money for the work we do. We're asking to be paid with a two-step deal versus a one-step. We're getting asked to get paid for rewrites. That's the work. That's the job. We're asking to be paid for the re-air and reuse and success of our work, as has been the case in the past. The studios don't want to do that anymore. They're done paying as fairly as they were paying 16 years ago.

Alex O’Keefe on the picket line. Photograph by J.W. Hendricks

Josh: In a lot of instances, we read all these headlines about [streamers] producing a whole series that they then just shelve for a tax write-off. A lot of people have a hard time even moving up to the next rank on a writer/producer ladder because nothing they've done gets seen. It's really difficult, and it feels like these companies are forgetting who's generating this value. The creative people, not just the writers and performers, but everyone across the board who does the work, the crews and the editors, and not the CEOs. They're forgetting who it is that makes them money. Just because they write off an expense on their taxes and it makes the stock price go up, doesn't mean that the company is more valuable or has produced any more value other than shareholder value. It’s not an indication of a healthy, thriving entertainment company if they're generating value by laying people off and ditching projects that they've invested millions of dollars in, rather than creating things that people get to see and pay money for, and enjoy and enrich their lives.

Alex: In Hollywood, the quiet fact is some of the most successful people come from generational wealth, so they're able to be supported in the downtimes. In Hollywood, there are up times and there are downtimes for every single career. You look at Robert Downey Jr. — he spent years just completely out of the business. That's natural. You can't prevent that. No one's always succeeding. But, I don't come from generational family wealth, and it's pretty hard to write from a space where I'm behind in rent, I can't get good groceries, I'm eating beans — the whole starving artist stuff.

If I'm writing for TV shows and big producers, I expect to get paid a sustainable wage, not asking for a million-dollar deal, just anything that can help me pay for groceries and rent. That's what's so sad to me, is that all we're asking for is to survive.

On The Bear, it was eight weeks of my life and $43,000 or so, you split it between taxes and agents and all. If that's your only gig, it's hard to make a living. If you don't get any residuals, then of course you have to take other jobs. I have friends who are on FX shows with second jobs while they're working on the show, which is unimaginable. If you know the level of work and mental energy expected of a prestige television writer, that system has to change because it makes it harder for us to produce value for companies.

We’ve had this business for a hundred years where you could be in a room and pitch, “It's like Jaws, but it's Bigfoot,” and the producer would be like, “A million dollars! Let's get some cocaine in here, folks!” And that was it. Now, you have to have multiple drafts of a screenplay. You have to write your own Bible and your own visual pitch deck. Sometimes, you have to cast and package your own project. All the burden of producing has been put on the writers. And if you don't have any connections, of course, you're not going to be like, “Oh, let me just call up Brad Pitt, I think he’d love to do this.” That's what producers are for, and that's why they get most of the money. Now, we’re doing a bunch of free work, and even at the end, we'll get a small amount of money, and they could still just replace us at any. Even if it's our own project, our own IP, they could just replace us with another writer if they feel like we're being difficult. There are good producers, and there are bad producers, there are good studio execs, and there are bad studio execs. It's a systemic issue.

Josh: Yeah, I completely agree. The development stuff is really tricky, working on multiple drafts of something that aren't contractually considered drafts. It's just, “Hey, let's get this into shape,” is such a familiar story. “Oh, let's just take another pass at this and get it ready.” Well, that's more work. That's what the job is — doing the writing, taking that extra pass, and getting it ready to go. Alex is so right about these residuals. You’re getting paid for these companies to exploit the work you've done in additional ways, and they're making even more money. This isn't just them handing you money out of nowhere. It's because they've found an additional revenue stream for your work. That's what’s supposed to keep writers and performers solvent during these downtimes. Now that seasons of shows are shorter and you're working on a show for 8-10 weeks, then you’re already looking for another job. That's what carries you through, even just the job search, a career doldrum. To shorten these seasons and the amount of time writers are on a gig, and then not to give them the income that they've earned, in order to carry them through to the next job, is cruel. It breaks down the workers. People are in desperate situations, and they're not thriving. They're really scraping to get from gig to gig.

Alex: Hollywood is one of the most abjectly capitalist places I've ever seen. LA has people living on the streets and then people living up on the hills. 98% of us voted to go on strike. Who's that 2%? Those are probably people who are at the tippy top of our industry who don't fight for the minimum. They have managers and agents that can get them far above. That's why unions are so important for people who are always getting the minimum amount and can't negotiate. This is our time to negotiate. By the time we get offered a gig, it's take-it-or-leave-it usually. So we’re fighting for the minimum.

Josh: Income inequality isn't just an entertainment problem; it's an America problem, and it's a global capitalism problem. A few people making far more money than others is a symptom of the capitalist system we live in. How hard it is for Americans to afford healthcare is such an important problem outside of our industry. Like Alex said, the union is helping to level that off for people within the ranks. Obviously, I would like to see an America where there is more equality across the board, more financial justice, and economic justice. I also think that part of what a union offers is solidarity. The people who have prospered, the ones that are showing up for the rest of us, the ones that have a microphone in their face and are like, “I'm fighting the fight for the people making minimum. I'm out here with them.” So the idea of us fighting amongst each other to go like, “Well, I don't think Tom Cruise should make as much money as Tom Cruise makes.” That's certainly a conversation to be had, but it's not necessarily a conversation about this contract.

Alex: Yeah, some of my biggest supporters have been showrunners who made it decades ago. They made their money, they got the residuals. Mark Blattman from Boy Meets World, Mike Royce from Everybody Loves Raymond – they’re are out there every single day at those pickets, and with those knees. We’re all artists, and we're all writers, and we have that solidarity.

Josh: People before us did this for us. We're doing this for ourselves and for the next generation of people, of writers and workers. I'm running for my third term on the WGA [East] council, and the elected officials help guide the direction of the union going forward and help set priorities. I'm really proud of the work we've done, and the West as well. Some of what the council has prioritized is the agency's action to end packaging. Agents were just profiting off of selling, and not incentivized to negotiate on behalf of their clients as is their fiduciary duty. On the East Coast, we restructured the way our elections happen and the way that things work so we could keep organizing members across workplace sectors. We don’t just have film & TV in the WGA East, we have online media and broadcast journalists, and we all kind of work together, but allow a degree of autonomy on the council and how those branches are self-governed as well.

Alex: I didn't expect to run for the WGA West board at the beginning of the strike. I was broke and just thinking about surviving, but I went to a strike authorization meeting where we authorized the strike, and we had the space for public comment. I was hearing a lot of fear, and I wanted to remind people why we're doing this. I went up there, and I talked about my experience on The Bear. I felt like sharing this was going to damage my career, and maybe it will in the long run, but at that moment, at least, I looked around, and my fellow writers were standing up for me and applauding me. That's when people started talking to me about the board and saying, “Hey, you should think about running for the board to be a voice for the low-ranking writers who don't usually have a voice in those spaces.”

I think if you're running a campaign just to win, it's the wrong way to campaign. You should always run a campaign to spread a message. Win or lose, you've planted seeds in the minds of people. Look at Bernie Sanders. He lost both times. He tried to win the presidency, but he inspired a movement of young progressives and got us talking about things that we weren't talking about before, like Medicare For All.

I built a platform, having talked to many people on the picket line and in one-on-ones, called Build a Better Hollywood, which has four points — to grow the movement by doing more organizing and turning our members into labor organizers. To defend diversity. To Smash Monopoly – there are six corporations that control 90% of the media industry, choking out all the life of our art. And finally, to have healthy workplaces for all.

Josh: It's part of the same struggle of working people against corporate interests. The Writers Guild sent a contingent to LaGuardia Airport when the American Airlines Flight Attendants Union announced their strike authorization vote, which is 99.4% with 93% participation. People are sick of taking shit. There was a flight attendant solidarity picket in New York City, with the flight attendants coming to SAG-AFTRA and WGA picket lines. We had a huge AFL-CIO day of solidarity with the laborers. This isn't just, we’re doing this, and they're doing this separately. People see that this is part of a bigger movement. We're part of this bigger thing.

Alex: Many people are just starting to realize that the American labor movement is having a moment, but all this has been the result of over a decade of organizing from the rank & file of these movements. With Teamsters, UAW, UTLA, and more.

You see it in Hollywood, too. There's been deep partnerships between the bosses, the CEOs, the corporation, and some of the unions, and there’s been corruption. Those at the top of some unions have been able to sustain a good life while people at the bottom wither away and don't have democratic rights.

Josh: Coming in as a comedy variety writer, working in late-night and coming to the council that way, a big chunk of the East membership works in that field, but it's still a pretty small slice overall of our membership. You kind of have to make a lot of a ruckus to get heard internally historically. And I think that we have a lot of great representation. Comedy variety writers on streaming shows essentially don't get residuals, and there are no minimum salaries. It's dismal compared to the same protections on network or basic cable or even pay cable. We’re bringing awareness to that. I think that the writers in the East and then Adam Conover on the board in the West have been diligent and effective in bringing awareness to this. As much as we're fighting for what concerns feature writers and dramatic and narrative TV writers, we have these other parts of our contract that need a kind of specific attention.

Alex: WGA East represents a whole array of writers, people who are historically exploited, like a lot of digital internet writers, digital workers, journalists, and a lot more comedy variety writers on the East Coast than on the West Coast. WGA West represents people who are often in writer's rooms, and most of those episodic series writers' rooms tend to be in LA. WGA West is Hollywood, baby. This is where the Dream Factory is.

Josh: In the two different guilds, the big difference that always jumps out to me is the breadth of writers that we represent in the East, which I think is a really wonderful thing that we do. I'm so psyched that we've gotten union contracts for people in all sorts of digital media shops and broadcast news. The other difference is our numbers are smaller. Being in New York, there's less of the industry here than in LA. It feels more tight-knit because it's so small. The way that's manifested during the pickets has been really interesting because a greater concentration of our picketing was going to individual production locations, sound stages, location shoots, and picketing with smaller numbers, even before SAG-AFTRA’s strike. Our two guilds work closely together and there are people who live in LA who are part of the WGA East and prefer their East membership or people who have moved to New York but still belong to the West, where they joined. It's very collaborative and collegial, but those are some of the key differences for me.

Alex: We work together, but it's technically two separate guilds. We're all the Writers of Guild of America together though. This contract is for all of us.

Josh: This strike represents all the writers or all the television, film, and entertainment writers that work in both guilds.

Alex: We negotiate together. The negotiating committees are made up of both guilds.

Alex: We've reached a point in the strike where people are really falling off a financial cliff. It's September now, and we know next month is when they [AMPTP] determine that many of us will lose our apartments and houses. That's when they think that their hands are going to be the strongest. If we want to be able to go into those negotiations with an equally strong hand, we need as much solidarity as possible. Our power is in our solidarity. If you can donate, it will help us keep this fight going and keep the lowest-ranking people in the guild able to stay involved in the fight and stay out on the picket line.

What we are asking for is nothing revolutionary. What we’re asking for is a standard that has been in this business for decades longer than I've been alive. We're asking for 2% of profits, a small fraction of a percent of the revenues that we generate. If the rest of Americans see that they can take on Apple, Amazon, and Netflix, then maybe they'll start unionizing with the Amazon Labor Union with Chris Smalls. Maybe they'll start fighting back en masse.

Our fight is your fight. I want people to realize there's no neutrality in this era. If we don't all stand up, we're all going to fall together. This is the moment to unite and realize that all of our fights are interconnected, and we all must have solidarity with each other.

Josh: That's such a beautiful way to look at this and a crucial way to look at this fight. If there's anybody who has read this far and is still in doubt, one side is asking for what amounts to 2% of the profit. Not even the revenue, not the intake. This is after expenses, after everything, just the profit that we generate. We've asked for what amounts to about 2% of that so we can afford to stay in our homes, that we can afford to have families, and that we can earn into healthcare. That's what we're asking for effectively. And the other side is saying, you don't deserve that. At an elemental level, that’s what this fight is about. It's a fight that's familiar to a lot of people across many industries, and it’s not complicated to me.

✦