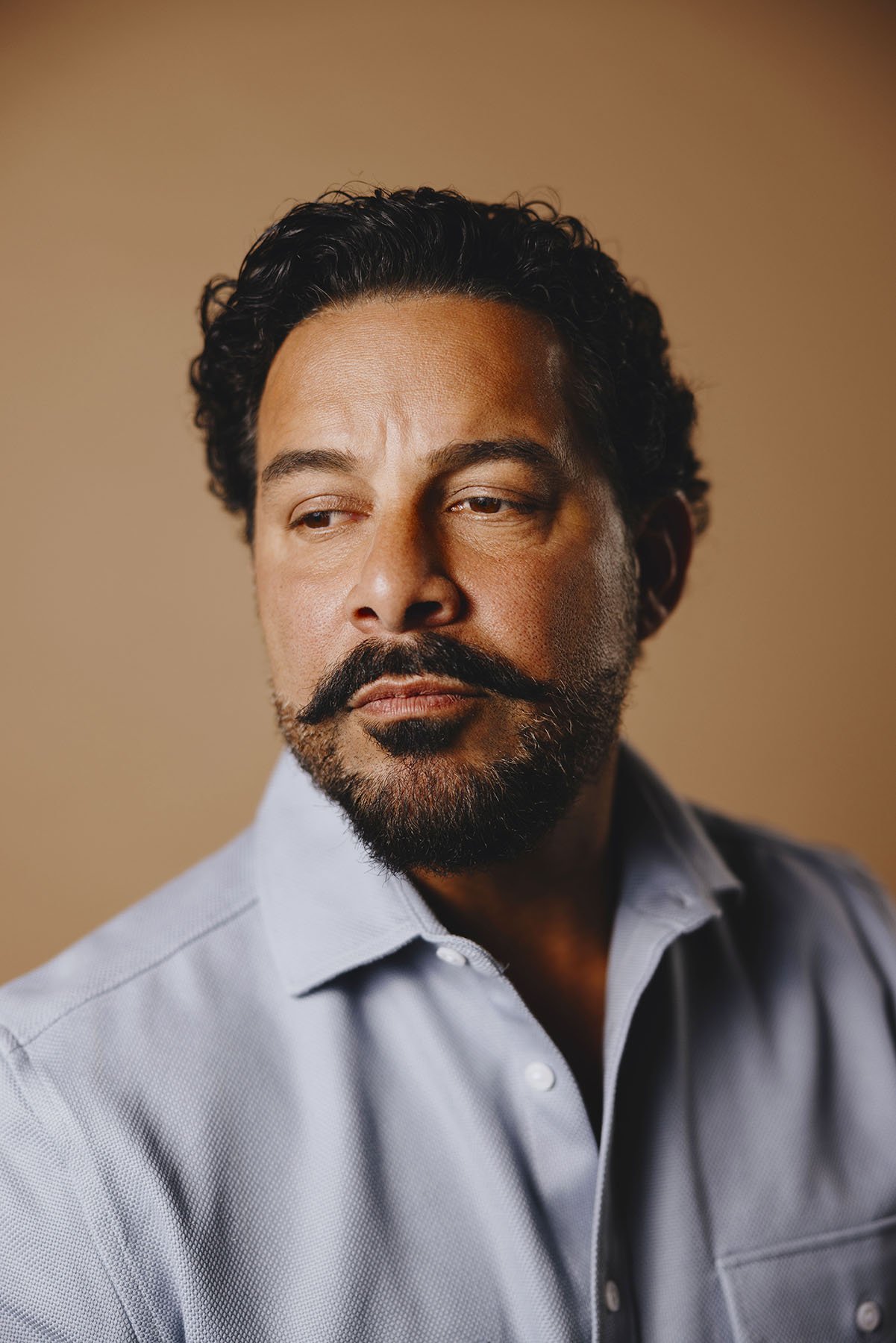

Jon Huertas

DISCLAIMER: We do not represent SAG/AFTRA or the WGA in any form. The following are individual opinions only. Please see the SAG/AFTRA or WGA websites for current information on the strikes. Read our #UnionStrong Statement here.

In Conversation with Jon Huertas & Phil Klemmer

Photography by Nolwen Cifuentes

Jon: I was interviewing for a directing gig this past season on a show called The Company You Keep. I had an interview with Phil, he was one of the showrunners on the show. While we were in the meeting, they asked me, “What else you got going on?” I was telling them about a couple of projects that I had been developing. One of the projects I was working on, I was basically shit-talking the town where I went to high school, saying how much I hated it. I created a show about that — what if I ended up having to move back to this town that I fucking hated? And Phil was like, “Where is this town?” I was like, “It’s back in Virginia. It's a small little historical colonial town no one's ever heard of.” He's like, “What's it called?” “No one's ever heard of it, Winchester.” And Phil says, “I grew up in Winchester.” I was like, oh, shit. I hope he doesn't love Winchester.

Phil: I was 99% sure that somebody had told you that and that it was an elaborate prank. There's no way this guy's from Winchester, Virginia. That's crazy.

Jon: That's how we met, and then I got the gig. I directed a couple of the episodes.

Jon: We were both in town for the last strike. I’ve been here for close to 30 years. I think you're very similar.

Phil: I got here in ’95. For me, the thing that's remarkable is that in the mid-90s, LA was very cheap. There was like a real estate bust going on, yet the economy was doing well. At the time, Tarantino and that sort of rebirth of the indie movie was very much the zeitgeist. So everybody who moved here wanted to be making the next Reservoir Dogs. There was this real excitement. I was working for Michel Gondry, the French director, at the time. They were spending $5 million on music videos.

Jon: Now they’re spending $5,000.

Phil: Nike commercials, you know, there were just all these incredible directors. To be an assistant was to make $500- $750 a week, which is exactly what people now make now even though inflation has tripled the cost of living.

Jon: But back then, you could rent an apartment for $400 a month. If you were making $500 a week, you were doing pretty good.

Phil: You were doing great. LA had that bohemian culture. You could come here, and you could be an artist and live a very good life. And if you had the good fortune to get on a TV show — which at the time was where dreams went to die. If you couldn’t make it in features, it's like, God, I guess I'll do TV, but you made such good money on residuals. You get one show in the air, you are done. You could retire.

Jon: To see the business side of it change, how TV is made, it’s why we’re in these strikes now. It’s not fair because now creators aren’t rewarded for their work.

Phil: Our compensation is tied to episodes. That used to be 22-24 episodes. Now it’s six or eight. And the paradox is that those six or eight episodes take longer to produce than the 22 or 24 used to. So you’re seeing this diminishment of your salary, especially for young writers. Or they're paid a guild minimum, which most people look at that money, and they're like, oh my God, that's a fortune. And it is a fortune if you were paid that every week for the rest of your life. But the truth is, writing is like being an athlete where most athletes, they blow out a knee.

Jon: Or they get traded, they get old. An 8 to 10-episode series is four or five months of work. Then there's an exclusivity clause built into our contracts where if they don't cancel the show right away, the actor and the writers are beholden to that contract. You can't go and work on another show. You can’t make a living because you're waiting for this show to be either canceled or go back into production.

I know this actress working on a show, Being Mary Jane, for BET. She was a series regular, she worked before that as a bartender. She got this job and shot for six months. But because of the schedule, they weren't coming back into production until like 18 months after they ended. So, she had to go back to the bartending job. People would come in and see her and say, “Hey, you, that lady on Being Mary Jane?” She's like, “Yeah, do you want a fucking cocktail or anything?”

It didn't use to be like that. It used to be, when you were on a television show, like in the 70s, 80s, 90s — when we got here — even the early 2000s, you could make a good living. Because everything was network, and networks weren’t doing anything less than 13 episodes.

What we all are doing by striking and picketing is trying to change the contracts to modernize how we get compensated for our work. The business has changed, audience viewing habits have changed, and we have to change with it.

Phil: The studios have really performed badly, so they are crying poor right now. During the pandemic, there were record profits for all of the studios because all anybody had time to do was watch TV. During that time, a lot of these giant companies decided that they wanted to merge. You had companies like Discovery who bought Warner Brothers and took on $50 billion in debt. These giant companies combined in ways that normally would've been considered illegal according to antitrust law with vertical integration. They all started moving away from the business model of producing and selling, which is basic capitalism where I have a product, you want it, you'll give me X money. It costs me less than that to make it, and I make a profit, and all the shareholders are happy.

The two things that went wrong were that everybody chased Netflix down this dead end of it being all about subscribers. Netflix made it seem like they had bottomless pockets, and they did when they were getting their content from other people and not making original content. Then everybody decided, oh, we’re going to do what Netflix is doing and keep all our content to ourselves. And that didn't prove to be a viable business. They took on debt and chased this dummy business model because they're dummy business people. Then they cry poor.

There are so many different ways that you can make entertainment more inexpensive. We could look at the budget, and we could come up with a thousand ways to do it for cheap, you know? Some of my favorite pieces of art were done under financial duress. I think it's great to have parameters. We don’t need to do James Cameron movies. The first impulse should not be to save money by giving the creatives behind this thing less. Instead of thinking about what other kinds of stories we can tell — it’s no, let's pay the people last.

Jon: We've seen now that almost every network has its own streaming platform. The way it used to be in network television is you have a successful show, and you make it to, say, a hundred episodes. Now you're allowed to sell that show and syndicate it. And that makes everybody a little bit more money, you get residuals through that for writers, actors, and directors. But now that networks have something like Hulu, it’s a streamer. They don’t do syndication anymore, it just lives on Hulu, and they can take it off whenever they want to. So that syndication model is gone.

Phil: A studio like Warner Brothers was able to sell to any network anywhere. As soon as the streaming wars started, everybody started holding onto everything for themselves. I always liken it to the Cold War, where it was us versus the Soviets — we’re gonna spend you into the ground. The problem is when you get into that mentality with Silicon Valley money, whether it's Apple or Amazon. If you're one of these legacy studios like Disney, these tech companies are like, we're going to spend you into the ground. How can you keep up with a business where, for them, the filmed entertainment is just an afterthought, a little hobby?

Jon: Apple TV+ is literally their side hustle. Us being on strike, they're probably laughing at us because we're posting all these photos on Instagram from their iPhones.

Phil: I don't know if this is true, but somebody had written it on a strike sign, but I'm gonna preach it as gospel. It was saying that for Apple to reconcile the demands of the Writer's Guild, according to the sign, it was something like $27 million, which, if you do the math, $27 million is definitely what they make in profits within the time that I can look at my watch. I can't hold my breath, but I can definitely go to bed, and when I wake up in the morning, they will certainly have made that much. For them worldwide, they can write a check. It's not a problem. The problem is that they're bargaining alongside all these other companies that have very disparate incomes.

Phil: We’re dealing with real existential issues with compensation. At least on the writer's side, most of that is tied to residuals. It also has to do with span issues and the size of the writer's rooms. They want writer's rooms to be small. They want to use mini rooms instead of real rooms. The truth is, the mini room is creative work that is done at the inception of the creative process, which anybody who's done this kind of work will recognize is the most important.

If anything, you should pay a premium for the work that is done at the beginning of telling a story. You’re creating the foundation that everything will follow. They've come up with this disingenuous kind of means of being like, “We're just spitballing guys. It's not a real room. It's a mini room.” And they pay everybody who's in a mini room a guild minimum. After 20 years of working, you suffer the humiliation of them saying, “Nope, you get paid the absolute minimum amount of money we can pay you to work at the most important part of the creative process.”

If you were to look at the pie chart of the writing of a TV show or movie, it's a very modest slice of the pie. Most people would argue that it would be money well spent because spending on professionals to live a dignified artistic life leads to good TV, movies, and media.

Jon: For me, I think the writer's room is one of the most important aspects of television right now. I disagree with mini rooms. I think there should be full writer's rooms because when you have a diverse cast of characters, you need to have voices in that writer's room, protecting the integrity of each one of those characters based on what those characters’ backgrounds are. Whether it's ethnic, sexual identity, or other aspects. I've been on shows where they didn’t have any Latinos in the writer’s rooms. And my character's voice is not protected. As an actor, I'm not in the writer's room, I'm on set. I can't necessarily help guide my character's journey from the point of view of being Latino. For me, it's important to have a full writer's room on every single project. When you don't have a diverse writer's room, you don't have deep development for every character.

Phil: Most people came to this industry hoping that they could make a living. They took an enormous risk to do so. Against all odds, two guys from Winchester, Virginia, we came here with our little gunny sacks over our shoulders. I had the stick with the little bag.

Jon: Me too, I had a piece of straw, just hitching on the back of a flatbed.

Phil: All you want really is to be able to continue to make that living. And it's a wonderful job to be able to tell stories.

Jon: It’s a dream job. Not a lot of people get to say that they do their dream job. That doesn't mean that you shouldn't be able to survive just because it’s a dream job. We should be allowed to fight for what we think is fair.

Phil: Until the machines replace us. Until Skynet comes to town.

✦